Managing and organising collaboration in an online community is sometimes a problem. Most collective action does not achieve the desired results for many reasons. So, instead of providing a how-to checklist, we have used a case study of a one-off success story, the Pink Chaddi campaign. These one-off success stories are important because they help us get a sense of the elements and conditions needed for effective collaboration and collective action in online communities.

Managing and organising collaboration in an online community is sometimes a problem. Most collective action does not achieve the desired results for many reasons. So, instead of providing a how-to checklist, we have used a case study of a one-off success story, the Pink Chaddi campaign. These one-off success stories are important because they help us get a sense of the elements and conditions needed for effective collaboration and collective action in online communities.

In this post, I’ll outline three lessons that activists and marketers can learn from the Pink Chaddi Campaign.

Lesson 1: Build your campaign around the social, cultural and political traditions of your identified target group. Then, give it an interesting, funny or irreverent tweak to help it stick.

Journalist Nisha Susan set up The Consortium of Pubgoing, Loose, and Forward Women on Facebook and urged women to send pink panties to Pramod Mutalik, the head of the ultra-conservative Hindu group Shri Ram Sena, in order to shame him into backing down from his threats to disrupt Valentine’s Day celebrations.

With its unconventional choice of name, The Consortium of Pubgoing, Loose, and Forward Women on Facebook purposely created a strong sense of us versus them. It reached out to the small minority of men and women in India who are amused by the irony of a woman being called ‘Pubgoing, Loose, and Forward’ in the same sentence. It also purposefully distanced itself from the Indian mainstream which still wants its Bollywood heroines to be virginal.

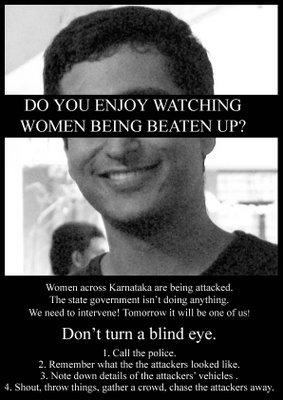

The Pink Chaddi Campaign tapped into the nationwide outrage against Shri Ram Sena after its activists beat up a group of young women in a Mangalore pub, claiming that the women were violating traditional Indian values by wearing Western clothes and drinking alcohol with men (Wikipedia). It’s important to point out however, that this outrage was mostly limited to a small but increasingly out-spoken section of Indian society: young men and women in cities, who tend to be privileged in family background, education, and work. These people most often come from liberal families (or have broken away from family ties), work in the new economy sectors of media, entertainment and technology, and have free time to spend socializing with friends and strangers in online communities and in neighborhood shopping malls.

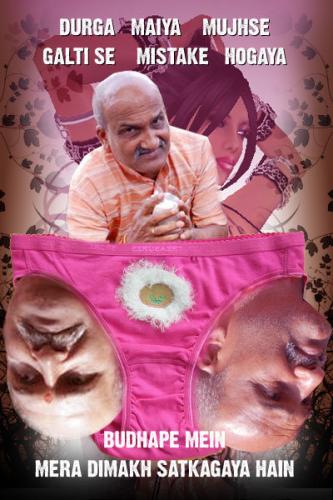

The choice of sending pink panties to Shri Ram Sena was another way for these people to position themselves as different from the more conservative mainstream. Chaddi means ‘underwear’ in several Indian languages, but combined with the choice of colour — pink — it essentially means pink panties. Some participants in the campaign even suggested that the act of sending pink panties was a strong statement that Indian women are ready to put aside their sense of shame and fight for their rights. At the core of the campaign was the idea of reversing the sense of shame. The Shri Ram Sena wanted to shame Indian women into submission. The gift of pink panties was not only a defiant statement against being shamed (”we won’t be shamed”) but also struck at Shri Ram Sena’s own sense of maleness (”you should be ashamed because you have in your possession women’s pink panties”).

The choice of sending pink panties to Shri Ram Sena was another way for these people to position themselves as different from the more conservative mainstream. Chaddi means ‘underwear’ in several Indian languages, but combined with the choice of colour — pink — it essentially means pink panties. Some participants in the campaign even suggested that the act of sending pink panties was a strong statement that Indian women are ready to put aside their sense of shame and fight for their rights. At the core of the campaign was the idea of reversing the sense of shame. The Shri Ram Sena wanted to shame Indian women into submission. The gift of pink panties was not only a defiant statement against being shamed (”we won’t be shamed”) but also struck at Shri Ram Sena’s own sense of maleness (”you should be ashamed because you have in your possession women’s pink panties”).

Consciously or unconsciously, Nisha Susan had designed the perfect campaign that encourages participants to get their friends involved or to share it with their friends. The pink chaddi campaign was not only relevant for its target audience – urban, educated and liberal Indians -, it was also funny and irreverent. An ironical inside joke like this can often turn out to be the perfect way for getting individuals to share the campaign with people close to them.

Lesson 2: Build virality into your campaign – make your campaign easy and fun to spread around. Choose a compelling message that users will want to share. Then, use a platform that makes it easy for them to share the message.

A great viral idea, in itself, isn’t enough. It also needs to be packaged into a compelling and easy to share message. That’s where the brilliantly designed Pink Chaddi Campaign Poster comes in. Nisha had first designed the poster herself by photoshopping an image of a chaddiwala and later asked her designer friend to redesign the poster. It was simple both in its design and its symbolism. Take a retro Hindu calendar with an Om, replace the Om with a pink panty, add some retro fonts and you have the perfect poster that triggers Bollywood, Hindutva, and irreverence at the same time.

A great viral idea, in itself, isn’t enough. It also needs to be packaged into a compelling and easy to share message. That’s where the brilliantly designed Pink Chaddi Campaign Poster comes in. Nisha had first designed the poster herself by photoshopping an image of a chaddiwala and later asked her designer friend to redesign the poster. It was simple both in its design and its symbolism. Take a retro Hindu calendar with an Om, replace the Om with a pink panty, add some retro fonts and you have the perfect poster that triggers Bollywood, Hindutva, and irreverence at the same time.

The choice of Facebook, instead of Orkut, as the social networking platform was also purposeful symbolic positioning of “us versus them”. Almost two third of active Internet users in India use Orkut, whereas Facebook is primarily used by a more metro-centered elite crowd, who are often introduced to it by friends in US universities. For the highest outreach, the campaign should have been present on both Orkut and Facebook, but it strengthened message of being against the conservative social majority by exclusively using Facebook.

Facebook is also the perfect viral platform, with its hyperactive news feed. Every time a user joined The Consortium of Pubgoing, Loose, and Forward Women on Facebook, an announcement showed up in the news feeds of all their friends. Members could also actively invite their friends to join the group.

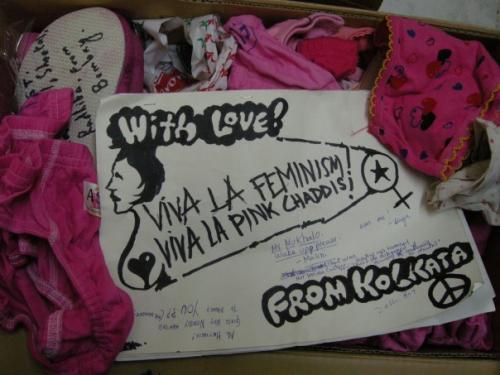

The campaign also asked group members to share pictures of themselves with the pink panties they were gifting, and many did, both on the Facebook group and on their own personal blogs. This was an explicit viral element that also helped the campaign gain popularity. Assuming that the average group member has 200 friends, up to 10 million facebook users were exposed to the campaign. Even if we allow for a high degree of duplication in the friend lists of members, it will be safe to say that millions of Facebook users saw the campaign in their news feeds.

The campaign also asked group members to share pictures of themselves with the pink panties they were gifting, and many did, both on the Facebook group and on their own personal blogs. This was an explicit viral element that also helped the campaign gain popularity. Assuming that the average group member has 200 friends, up to 10 million facebook users were exposed to the campaign. Even if we allow for a high degree of duplication in the friend lists of members, it will be safe to say that millions of Facebook users saw the campaign in their news feeds.

Lesson 3: Design your campaign to translate online engagement into offline action. Make it easy to take collective action by breaking it down into smaller individual actions that can be taken independently, but that work together within the whole campaign.

The Pink Chaddi campaign was also designed to trigger offline action, gifting pink panties to Shri Ram Sena on Valentine’s Day. Finally, almost 2000 panties were sent to Shri Ram Sena, against a target of 5000.

The Pink Chaddi campaign was also designed to trigger offline action, gifting pink panties to Shri Ram Sena on Valentine’s Day. Finally, almost 2000 panties were sent to Shri Ram Sena, against a target of 5000.

I think that the campaign was able to drive offline action, because it made the action both modular and granular – it broke down the campaign into smaller individual actions that could be easily done by one individual. It simplified the task of getting 5000 pink panties to Shri Ram Sena by asking individual members to do two things:

1) send one panty to the Sena and

1) send one panty to the Sena and

2) encourage your friends to do the same by posting a picture of you with your pink panty.

The address of Sena’s Hubli office was shared prominently on all campaign messaging and supporters were encouraged to directly mail panties to the address. Alternatively, panties could also be dropped at designated collection centers.

Compare this to the difficulties of organizing a protest march at a specific time and place, and it is plain to see that traditional models of protest cannot always benefit from the possibility of organizing collective online actions that consist of aggregated modular and granular individual tasks.

Finally, Nisha Susan displayed great media savvy by holding a series of press conferences to publicize the campaign. Nisha is a journalist herself with Tehelka and realizes that “participatory media is most effective when it is able to push up important stories into the legacy news media.”

Conclusion: Questions in the aftermath of the Pink Chaddi Campaign.

There are many unanswered question at the end of the Pink Chaddi Campaign.

The first question is: was the campaign really successful?

The answer is the universally unsatisfactory “it depends”. The campaign was undoubtedly successful in terms of creating reach and engagement but it’s not sure if it brought about any real change.

Let’s talk about reach first. More than 50000 users joined the campaign group on Facebook. More than 300 blogs linked to the campaign blog. More than 150 news stories mentioned the campaign. These are unusually high numbers for a grassroots online campaign in India. At the same time, the media attention also helped Shri Ram Sena and brought its leader Pramod Mutalik into national limelight.

In terms of engagement, the campaign generated interest amongst both men and women both in India and internationally. It also started a serious debate in both mainstream and participatory media over who gets to define Indian culture. At the same time, we must remember that the debate was limited to a small minority of Indian elites. I don’t think that the campaign changed the views of the Indian mainstream.

Finally, in terms of impact, the campaign did mobilize significant offline action. Getting Indian women to send 2000 pink panties to Shri Ram Sena is no small achievement. The public debate around the campaign also forced Shri Ram Sena to back down on its threats of disrupting Valentine’s day celebrations. However, as many observers have pointed out, the campaign didn’t really change anything. Public opinion on Shri Ram Sena is still divided in India and most of its leaders are unlikely to be punished by law.

The second question is: what happens now that Valentine’s Day is over? Nisha Susan is trying to maintain the momentum of the group by asking them to stake a claim for our shared culture by creating one minute videos about what Indian culture means to each one of us. It looks like a plan the might work, but only time will tell.